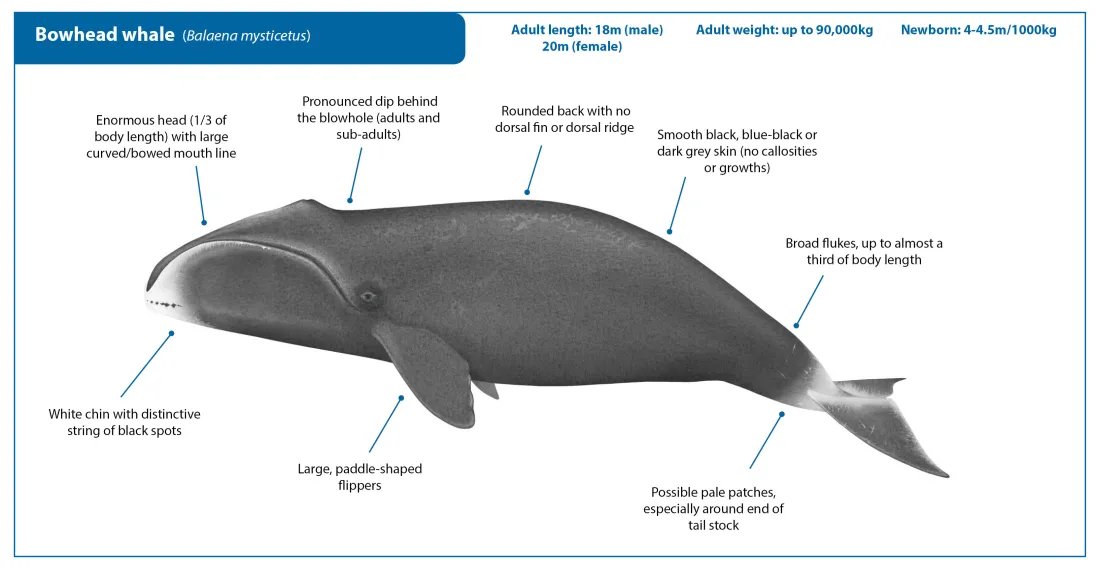

Bowhead Whale Balaena mysticetus

Bowhead whales are supremely adapted to a life cycle spent entirely in the freezing, or near-freezing waters of the Arctic and sub-Arctic. Found in both northern Atlantic and Pacific waters, the species has evolved thick skin and blubber for insulation and a source of energy reserves, an enormous, strong and bowed head that can break through ice up to 1 m thick, and an ability to stay under water for over an hour at a time to swim beneath the ice 1,2. Although the bowhead is not the largest whale species, it is one the heaviest, and certainly the longest-lived. Evidence suggests that individuals can live up to 150, and perhaps even as long as 200 years2-4!

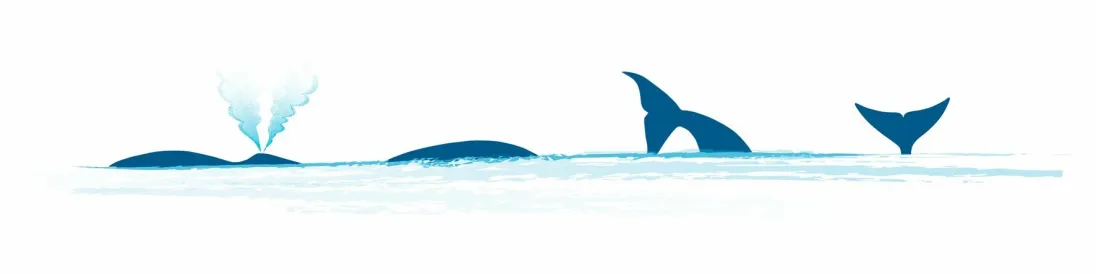

Once referred to as the ‘Greenland whale’, or the ‘Arctic right whale’, few commercial whale watching operations target this species because of its mostly remote habitat. However, because it is a predominantly coastal, shallow-water species, it can be viewed from shore in some parts of its range. Although not available to commercial whale watching, one of the longest standing population research projects on this species counts passing whales from an observation perch on a pressure ridge from the edge of shorefast ice in northern Alaska 5,6. The bowhead whale is also one of the few whale species still subject to an ongoing aboriginal subsistence hunt, managed by the International Whaling Commission.

Not to be confused with:

In the Atlantic, bowhead whales could, at first glance, be confused with right whales, which also have smooth black backs without dorsal fins. However, the two species heads are very different, as bowhead whales lack the distinctive white callosities found on the top of right whales’ heads. Instead bowhead whale ‘chins’ are white, while right whales have dark chins and undersides. In the Pacific, bowhead and gray whales overlap in the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas, but gray whales are generally much slimmer and lighter in colour, and have pronounced ‘knuckles’ on their dorsal ridge.

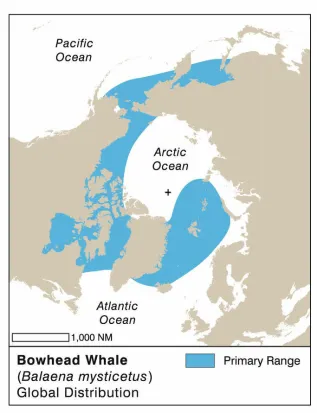

Distribution

There are currently four recognized stocks or breeding populations of bowhead whales: 1) A small genetically distinct population restricted to the Okhotsk Sea; 2) the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Seas stock (BCB) 3) the eastern Canadian-western Greenland Stock; and 4) the Spitsbergen Stock2. Throughout the species’ range, bowhead whales are generally found in waters shallower than 200m, and often close to land, or sea ice 2,7.

Bowhead whales do not migrate as far as many other baleen whales. They migrate between wintering areas where mating/calving occurs to summer feeding areas, a distance of ~1500km for BCB bowheads. The spring seasonal movements are typically northwards through the sea ice and along the ice edge to higher latitudes in the summer, and returning to more southerly areas of their range during the winter8,9.

Native to the following countries: Canada; Denmark (Greenland); Iceland; Norway; Russian Federation; United States (Alsaska)

Vagrant: France; Ireland; United Kingdom;.

Biology and Ecology

Feeding

Bowhead whales feed predominantly on copepods, krill and other zooplankton, although there is some evidence that they can also feed on fish species, and bottom-dwelling crustaceans2,7,10.11. Bowhead whales often skim feed at the surface of the water, using their very long baleen plates (up to 5-6m) to filter out prey, even from less dense aggregations of zooplankton. However, they can also feed in the middle of the water column, or even along the seabed7.10.

Social structure, reproduction and growth

Bowhead whales are normally found in groups of three or fewer animals, but can congregate in larger numbers where food is abundant and/or while migrating1. Mating is assumed to occur in March, and calves are born the following April or May after a 13-14 month long gestation period 2,5. Females do not begin to have calves until they are roughly 25 years old12, and only give birth to one calf every 3-7 years13. Calves are around 1000 kg at birth and must grow and acquire insulating blubber as quickly as possible. Adult whales have a blubber layer up to 50cm thick, and calves grow more quickly in their first year than any other time in their lives8,9. Calves are weaned between 6 and 12 months2,9.

Bowhead whales, like many baleen whales, also use sound to communicate under water 2,14. This renders the species vulnerable to disruption of feeding and communication when loud noises are generated from seismic surveys or other shipping and/or industrial activity in their habitat15.

Research, threats and conservation status

Bowhead whales sometimes bear the scars typical of killer whale attacks, which are the only known natural predator of this robust whale species2. Human-induced threats to bowhead whales include entanglement in fishing gear1,6-18, and increasingly, ship strikes and disturbance from underwater noise related to expansion of shipping, fishing, and oil and gas exploration in the Arctic as ice cover retreats1,9-21. While bowhead whales may temporarily be benefiting from expanding feeding habitat associated with global warming and melting ice, it is unknown how this drastic change in habitat will affect populations in the long term22,23. One consequence may be the merging and blending of Atlantic and Pacific populations that have been separated for generations, as recent years has seen the two come into contact with each other with the opening of the Northwest Passage24.

Conservation status

Bowhead whales were hunted for centuries, first by aboriginal groups in the Arctic, and then commercially for both their oil and their baleen9,25. Commercial whaling for bowhead whales decimated stocks but has been prohibited under international conventions since the 1930s. Since that time the BCB subpopulation has been steadily increasing at a rate of roughly 3% per year6. That population is now thought to number roughly 16,000 animals (See this IWC site for updated population estimates). Numbers in the East Canada – West Greenland subpopulation are estimated at 4,500-11,00028 and is also probably increasing. The species is globally considered of ‘Least Concern’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species25. However, the other two stocks are less numerous. The East Greenland-Svalbard-Barents Sea and Okhotsk Sea subpopulations are classified as Endangered26, 27. The species is listed on Appendix 1 of both the Convention on International Trade in Endangered species (CITES) and the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS).

Bowhead whales are subject to aboriginal subsistence hunts in the US, Russia, Greenland and also Canada. The hunts in the US, Russia and Greenland are regulated by the International Whaling Commission (See this IWC table for annual catch numbers). The hunts in Canada are regulated by their Federal government in collaboration with Indigenous groups (Canada withdrew from the IWC in the 1981).

Bowhead whales and whale watching

Generally, as a 'shy species' located in remote regions of the Arctic and subarctic, bowhead whales are not often billed as the target of whale watching operations. They can be viewed during day-trips from a few locations in Canada (e.g. Baffin Island). The species also occurs in Greenland (Denmark) (esp. Disko Bay), and Norway (Svalbard), as well as northern and northwestern Alaska (the United States). Because those three Arctic subpopulations are often associated with the ice-edge, they are perhaps more likely to be viewed during live-aboard Arctic wildlife tours than day trips from these locations.

However, the situation is different in the Russian Federation. In the Okhotsk Sea, bowhead whales spend summers in the mainland bays near the Shantar Islands archipelago. The area is an emerging tourist destination itself, and the archipelago has recently started to attract whale watchers from Russia and other countries and is becoming an internationally recognised mecca for bowhead whale watching. Being a new type of tourism, whale watching is not regulated in the country, which raises concerns due to the endangered status of the Okhotsk population.