Irrawaddy Dolphin Orcaella brevirostris

Irrawaddy dolphins are not known to be particularly acrobatic or showy, but their history of close associations with fishing boats makes them approachable for dolphin watching in some areas of Southeast Asia where they are considered the main focus of marine tourism. Their preference for nearshore habitats associated with freshwater inputs keeps them resident in fairly restricted geographical areas, and therefore makes them easier to locate than some species that have wider ranging habits. But this habitat restriction also places them at great risk from human-induced threats like entanglement in fishing gear, habitat changes from coastal construction, pollution, and disturbance from vessel traffic1.

Not to be confused with:

Irrawaddy dolphin habitat overlaps with that finless porpoises, humpback dolphins, and bottlenose dolphins. While they are similar in size to finless porpoises, and have a similar rounded head with no beak, the presence of a dorsal fin will distinguish Irrawaddy dolphins. Irrawaddy dolphins are much smaller than humpback or bottlenose dolphins, and have no pronounced beak as both these species do.

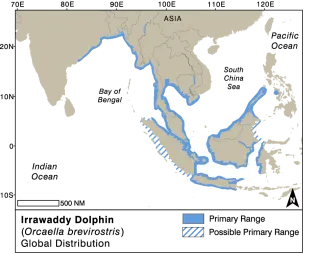

Distribution

Irrawaddy dolphins are patchily distributed throughout freshwater and coastal areas in Southeast Asia. The three main freshwater populations inhabit the Ayeyarwady, Mekong, and Mahakam rivers1. Coastal populations live in brackish or saline waters, and are generally associated with areas of freshwater input, such as river deltas, mangrove channels, and estuaries. A related species, the Australian Snubfin dolphin (Orcaella heinsohni) is found only off the North coast of Australia and around Papua New Guinea2,3.

Native to the following countries: Bangladesh; Brunei Darusssalam; Cambodia; India; Indonesia; Lao People’s Democratic Republic; Malaysia; Myanmar; Philippines; Singapore; Thailand; Viet Nam Snubfin dolphins are native to: Australia; and possibly Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

Biology and Ecology

Feeding

Irrawaddy dolphins appear to be generalist feeders, taking a variety of fish depending on their habitat. They are known to bottom feed and sometimes surface with mud on their heads or backs. They can also spit water while feeding, apparently to help capture fish. In many parts of their range, they are known to feed in close proximity to fishermen that are setting or retrieving their nets, and in some sites, including the Aeyerwaddy river in Myanmar, and Kuching, Sarawak, they are known to accept discarded fish thrown by fishermen as nets are hauled in4,5. Irrawaddy dolphins also appear to follow tides, moving inshore and into river mouths with high tides, and further offshore as the tides go out6-10, probably following the movements of the fish that they eat.

Social structure, Reproduction and growth

Little is known about Irrawaddy dolphins’ life history. They tend to occur in small groups of 2-6 individuals11, but larger aggregations have been documented in Sarawak4 and Thailand12. These larger aggregations are believed to be associated with mating. Gestation is thought to be about 14 months, with births peaking in the pre-monsoon season of April-June, but they may occur year-round.11

Threats and conservation

Irrawaddy dolphins’ main natural predators are assumed to be sharks13, but much more concerning are the many human-induced threats they face. As with all whales and dolphins, accidental entanglement in fishing gear, known as bycatch, is the leading source of human-induced mortality for Irrawaddy dolphins. This is particularly true in coastal areas where large-mesh gillnets are the predominant fishing gear used, as these are often set and left unattended for long periods of time, entangling dolphins as they travel or chase fish into the nets5,11,14,15. Agricultural and industrial run-off in areas of dense human habitation are also associated with high contaminant levels in coastal areas where Irrawaddy dolphins occur, and a recent study of six Irrawaddy dolphin populations documented high levels of skin abnormalities thought to be associated with poor water quality16.

Conservation status

There is no range-wide estimate for Irrawaddy dolphins, and few populations have been studied rigourously enough to generate population estimates. But where they have been studied, numbers are generally low (in the 10’s to low 100’s). A recent IUCN review of available studies and literature concluded that the threats facing the fragmented poulations throughout the species range merit a new Endangered status on the IUCN Red List17 and the species also carries a CMS Appendix 1 listing. Three riverine Irrawaddy Dolphin subpopulations (Mekong, Ayeyarwady, and Mahakam), one in Songkhla Lagoon in Thailand, and one in Malampaya Sound, Philippines are listed as Critically Endangered (CR) on the IUCN Red List.

Irrawaddy dolphins and dolphin watching

Irrawaddy dolphins are not usually acrobatic or showy, but they can be approachable by boat, perhaps through the long association with fishing vessels in many parts of their range, or perhaps simply because their feeding grounds are so restricted that they cannot afford to leave them even if disturbed by approaching vessels. As such, they are the main attraction of marine tourism in areas like Kuching, Sarawak, the Mekong River, Cambodia18,19, and the Chilika Lagoon, India where pressure from dolphin watching combined with other threats may be having a serious population-level impact on the population20,21. Here, as everywhere else it is extremely important that whale watching does not compound threats, but instead contributes to conservation by adhering to responsible whale watching guidelines.