Argentina: Península Valdés, Chubut

A multi-stakeholder, multi-faceted, adaptive approach to regulation of whale-watching

History and context

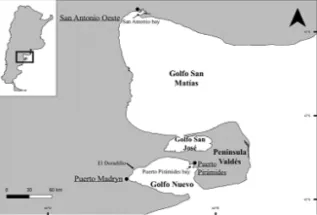

Whale watching in the Península Valdés region of Patagonia began in the mid-1970’s when boat owners took tourists out in small groups at irregular intervals to view southern right whales using the area1. At the time, southern right whales were severely depleted after years of hunting, and it was initially rare to see mothers and calves in the bays surrounding Península Valdés. However, as more industry and more tourists came to the region, whale watching activities steadily grew up through 1987, when the government first started to track statistics on the industry.1 At the time, Argentina’s participation in the International Whaling Commission and the 1974 declaration of the provincial marine park of “Golfo San José” (via Provincial Law No. 1238), were the only regulations in place to protect whales in the area.

Right whales were first protected by the 1931 Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, which was implemented from 1935 onward. Following this, and the global moratorium on whaling (1986), the southern right whale population off the coast of Argentina began to increase rapidly. By 1980 it was estimated that 168 breeding females were using the area, increasing to 328 by 19902. The rate of population increase was estimated to be 7%, and there was a shift in the whales’ distribution to the inside of the Golfo Nuevo, off the coast of El Doradillo3, where densities were as high as 6.5 whales/km2. This rendered whale watching activities more reliable and more rewarding for tourists. Five local operators were in place by 1987, a year in which government statistics documented 5,214 whale-watch tourists. Over the next 13 years, the number of whale watch tourists increased by an average of 6,275 tourists per year to reach nearly 70,000 by the year 20001. Although the southern right whales are only present between June and December, a variety of other marine mammal species attract tourists in the “off season”: acrobatic dusky and other dolphins; elephant seals and sea lions; and the now -famous killer whales that launch themselves onto the beach to catch sea lion and southern elephant seal pups. Due to the nearshore (or onshore) distribution of many of these marine mammals, tourists can enjoy land-based wildlife watching activities as well as boat-based whale-watching. In 2006, 80% of visitors to Peninsula Valdes arriving between June and December engaged in whale-watch tourism, and over 61 million USD of revenue was generated either directly or indirectly for Argentina through whale watching tourism.4

Regulatory measures

This rapid increase in whale watching tourism in the 1980’s and 90’s led authorities to recognize the need for regulatory measures to protect both the whales and the tourists. In July 1986, Provincial Decree No. 916 (and its subsequent amending Decree No. 1127/91) established a registry of whale-watch tour operators, stipulating that a maximum of 5 licenses would be granted to operators for a maximum of 2 years at a time. The decree also established a registry for specialist whale guides and skippers, who could register only after having undertaken approved courses on basic whale biology and codes of conduct (vessel-handling) in the presence of whales.

In 1999 the Península Valdés was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site (ID 937) in recognition of its importance as a breeding site for southern right whales, as well as breeding populations of southern elephant seals and southern sea lions, and the unique hunting techniques used by killer whales in the area. This global status was followed by the establishment of the Península Valdés Natural Protected Area (ANPPV) (via Provincial Law No. 4722, then Law XI-20). In 2004 a clear management plan and enforcement procedures were approved and formally put into place, and a multi-stakeholder “Advisory Committee for the Service of Whale Watching” was formed to help monitor and provide feedback on implementation of whale watching within the protected area1. This body organized a series of multi-stakeholder workshops between 2004 and 2007. These involved tour operators, NGO’s, and local government representatives, among others, drafting new regulations and codes of conduct for whale watching in the region. This culminated in the 2008 implementation of Provincial Law No. 5714 (then Law No. XI-44), which stipulates, among other things:

That tour operators adhere to the guidelines for approaching whales established in the “Patagonian whale watching Technique” and that tourists follow “code of Good Practice Guidelines”;

- A prohibition on harassing, swimming, or diving with whales at any time of year;

- That tour operators visibly display the guidelines in English and Spanish, and that these be clearly communicated to tourists before they board vessels for tours;

- The maximum number of whale watching permits (6),

- The minimum duration of a permit (6 years);

- The maximum number of vessels operated at any one time by a tour operator (1);

- The maximum number of passengers allowed on a single vessel (70);

- The minimum duration of a trip (90 minutes - to avoid low-budget, rushed trips with high pressure to find whales fast and approach them carelessly);

- The types of groups that can be approached, and when (e.g. approaches to mother-calf pairs are prohibited before Aug 31 each year, when calves are deemed robust enough to be less vulnerable to disturbance).

- A tax to be paid by WW service providers, the revenue from which is used to support a Protected Areas Conservation System and research and conservation projects within the ANPPV;

- The establishment of an Under-Secretary of Tourism and Protected Areas as the authority empowered to administrate the new regulations, and the designation of the Argentinian coast guard as the body empowered to enforce the regulations and intervene in case of observed infractions.

With some minor adaptations between 2008 and the present (changes to the procedures for applications/tender for permits, length of permit duration etc.), these regulations and this regulatory framework are still in place today. Various shifts in both the Argentinian and global economy have affected whale watch tourist numbers in Peninsula Valdes over the years, but numbers remain more or less stable hovering around 100,000 tourists per year between 2006 and the present1.

The population growth rate for southern right whales in the region has also slowed5, with some inexplicably high numbers of deaths in some years6 leading some to wonder whether climate change or fluctuations in productivity are limiting food sources and the whales are reaching their carrying capacity (the maximum number that can be sustained by the local ecosystem) in the region.

A number of studies conducted over the years have confirmed that inappropriate approaches from boats can influence the behaviour whales and dolphins in the area, potentially having a negative impact on their ability to feed, nurse their young, or rest and socialize7,8. These studies support the need for well-defined and cautious regulations that minimize the number and nature of vessel approaches to whales and dolphins.

Lessons learned: Strengths and weaknesses of regulatory measures over time

On paper, the development of the whale-watch tourism industry in Argentina has many strengths, and appears to serve as an excellent model for regulation of whale watching in new areas. These strengths include:

- The early establishment of regulations and limits on the number of providers allowed to run tours in the region: The establishment of clear guidelines and limits while the numbers of operators were still low (5), prevented the unregulated growth of the industry. It would have been nearly impossible to close down businesses once they had been established. Similarly, the limits on the number of vessels each operator could run, and the maximum number of tourists per vessel, precluded an increase of vessel traffic and disturbance before it could occur.

- The establishment of protected areas through both national and international measures clearly defined the critical habitat for whales, and established clear boundaries for conservation measures and regulations designed to protect the whales. Whale watching operators and tourists are perhaps more willing to comply with regulations when they feel that they are privileged to be engaging in their activity in an internationally recognised area of importance. The protected area status has also ensured that the terrestrial area surrounding the bays has remained pristine and attractive to tourists4. The clear geographical boundaries of the protected area may have also made it more practical and feasible to develop management plans and regulations that could be administrated and enforced on a local, rather than a national scale.

- The involvement of many stakeholders in a consultative process to draft guidelines and regulations. The continued and direct involvement of the tour operators themselves in the drafting of regulations is viewed as a key strength, ensuring industry buy-in and acceptance of the guidelines, and their perception that these are reasonable and fair9.

- The establishment of clear regulatory authorities with the mandate to administrate licencing, permitting, and fees associated with whale-watching, and the clear designation of how any revenue collected from licensing will benefit the conservation of the whales and their ecosystem. This is backed by a clear mandate for the Coast Guard to help monitor and enforce compliance with the law.

- The continual evaluation of the potential impact of whale watching tourism on whales (and dolphins) in the area, and the assessment of findings against the adequacy of current regulations and their enforcement.

At the same time, however, there are some concerns about the system and its implementation on the ground, which may not be as perfect as it appears on paper. A recent study interviewed roughly 50% of the specialist guides working on whale watching tours, and learned that many tour operators find it difficult to respect the prohibition on approaching mothers and calves of the year before August 31st1. Because mothers and calves are generally found closer to shore, they are more readily encountered by tour boats, and are too tempting to approach, especially on rough weather days, when operators worry about tourists’ comfort and expectations. There is a perception that, in view of the population increases that have taken place since the original regulations were put in place, the ban on approaching mothers and calves should be relaxed1. It is not at all clear whether this would be supported by the research and conservation community, or the regulatory authorities. Nonetheless, the implementation of the study and its publication can be seen as a healthy review of the system in place, a respect for the tour operators’ concerns, and the system’s ability to adapt to new circumstances if and when necessary.

Since this case study was published in 2018, a new study has been published. See: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0141113619303253?via%3Dihub