Australia- Great Barrier Reef Swimming with little giants

History and context

Dwarf minke whales are an undescribed subspecies of minke whale that occur throughout the southern hemisphere and were first recognised in the Great Barrier Reef in the 1980s1. As the name would imply, dwarf minke whales are smaller than other forms of minke whale (less than 8m), and are recognizable by their distinct colour patterns which include swirls and blazes not present in other minke whales and a distinct white shoulder patch2.

The Great Barrier Reef off the northeast coast of Australia has been a popular diving and snorkeling destination for many decades. It was declared a World Heritage Area in 1981, and in 2016 it attracted 2.4 million tourists3. In the 1990s, as divers and snorkellers began frequenting the outer shelf Ribbon Reefs north of Port Douglas on live-aboard dive vessels during the austral winter, they began to experience close encounters dwarf minke whales. From the mid-1990s onward dive tour operators began to advertise ‘swim-with-minke whales’ trips. Although swimming with whales in Australia was generally prohibited, a limited swim-with whale program was officially recognized, endorsed and permitted by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority in 2003. A cap was set on the number of operators (maximum of 9 permits) that would be able to offer swim-with-minke whales tours: all of which have been based in the Cairns and Port Douglas region.

Permits are issued under the condition that all vessels interacting with dwarf minke whales comply with a Code of Practice, and contribute to standardized monitoring of all their whale encounters. The operators are encouraged to share additional data from their encounters (underwater photos, etc) with researchers conducting long-term studies of the whale’s population biology and behaviour. More than 20 years of close collaboration between the dive operators, Reef managers, and scientists from the Minke Whale Project at James Cook University has resulted in an improved understanding of the whales’ population, behavior and migration, and has helped to refine management policy to ensure that the swim-with activities are managed sustainably.

An unusual aspect of the minke whale swims, is that the majority of encounters are initiated by the whales themselves, which often approach a stationary vessel or swimmers/divers who are already in the water4. Passenger-whale interactions tend to be extensive, lasting an average of more than two hours5. To ensure the safety of snorkelers during in-water encounters, and to prevent whales being chased or harassed, it is required for the operators to put out surface ropes for swimmers to hold onto.4

While little is known about the whales’ population and life history outside of their brief aggregation each winter in the Great Barrier Reef, photo-identification studies have allowed researchers to recognize individual whales that are re-sighted within and across seasons6,7. Analyses of data on the distribution, frequency, and duration of encounters have shown that whales are reliably found in a limited number of ‘hotspots’ in the Ribbon Reefs, and individual whales have been observed returning to these same places year after year. Such hotspots have been targeted with increasing frequency by permitted live-aboard vessels, resulting in highly reliable interactions each June-July season.

Regulatory measures

Research conducted in the late 90’s contributed to the drafting of the first code of practice for swimming with dwarf minke whales 1999. This code was voluntarily adopted by operators in 2002, and was recognised by the Great Barrier Marine Park Authority when they issued the first permits to manage swim-with-whale tourism in the Marine Park in 2003. Since that time, permits have been a legal requirement to conduct swims, and the number of operators remains low to reduce the potential for cumulative impacts of human interactions on the whales.

The Code of Practice for minke whale encounters is based on research and observations of hundreds of interactions with the whales, and is designed to be adaptive, allowing it to be updated from time to time as new information or management issues emerge. The current code includes the following stipulations:

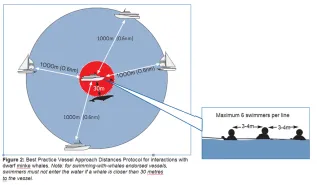

- Clearly defined vessel approach guidelines in line with the Australian national guidelines for whale and dolphin watching.

- Specific measures for vessels passing in proximity to other vessels that are conducting in-water interactions with whales, and a limit of one vessel interacting with a group of whales at a time.

- The requirement for an extensive briefing of participants before an in-water encounter, with an understanding that it is the operator’s/crew’s responsibility to ensure client compliance with the code.

- Detailed instructions for how crew members should monitor and manage the safety of passengers and the whales – including the deployment of up to 2 surface safety ropes (no longer than 50m), careful observation of whale behaviour and proximity at all times, and preparedness to call swimmers back to the vessel and assist their re-boarding at any sign of disturbance or risk to either the whale or the passengers.

- A prohibition for divers/snorkelers to swim directly towards a whale, intentionally approach it to within less than 30m, or make physical contact.

- A prohibition on the use of flash photography.

Lessons learned and recommendations for the future

There are concerns in the research and conservation community about in-water encounters with whales. Whales are large and powerful animals, capable of causing injury to humans with the sweep of a tail. There are also concerns for the well-being of the whales, particularly for those individual dwarf minke whales who return to the same site every year and may be the focus of repeated and lengthy encounters with humans during their stay8. Studies have documented the potential long-term impacts of tourism-induced changes to whale or dolphin behaviour9-12, and these potential impacts need to be considered for minke whales on the Great Barrier Reef as well. The Minke Whale Project has an ongoing role in monitoring the sustainability of the swim-with-whales activity, and many of the rules and recommendations in the Code of Practice and other related materials (e.g. interpretive materials distributed to each permitted boat each year, annual reports to government agencies) have been based on research findings and designed with the well-being of the whales as the first priority.

This case study presents a number of strengths and challenges for consideration:

Strengths:

- This is perhaps the best regulated and monitored swim-with whale or dolphin industry in the world13. Taking advantage of the predictable seasonal presence of dwarf minke whales, the tourism interactions have been well studied and well-regulated from their inception. Regulations were developed collaboratively by a range of key stakeholders, and are periodically reviewed and adapted as new knowledge and/or management issues emerge.

- Tour operators, researchers and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority have worked in close collaboration to monitor behaviour of operators, whales and tourists over time. Operators host researchers on their vessels, facilitating data collection, and enriching the experience for tourists, who can interact with, and learn from the scientists. The collaboration has facilitated the completion of four PhD studies with an additional five in progress, at least a dozen Masters theses, and several reports relevant to management (see the Minke Whale Project website for details).

- In turn, researchers help with pre-season training of vessel crew and report their findings back to the industry periodically though workshop. This model for engagement provides opportunities for stakeholders to express and discuss any emerging concerns and adapt requirements and management measures as needed. In some cases, this has led to voluntary agreements between operators that greatly exceed the regulatory requirement (e.g. an agreement to not purposefully swim with mothers and calves in 2006) which was later incorporated into the Code of Practice14.

- Researchers also provide tour operators and tourists with a range of educational support materials (e.g. posters, brochures, slideshows) that allow crew members and tourists to be better informed about minke whale biology, behaviour and conservation needs. Such interpretation has been shown to improve the satisfaction of tourists participating in the swims15.

Challenges:

- Anecdotal reports indicate that some non-permitted operators allow their guests to engage in in-water interactions with dwarf minke whales. Knowing that Australian regulations prohibit targeted swimming with whales, non-permitted operators may neglect to report their interactions with whales for fear of prosecution16. Furthermore their interactions are unlikely to be reported as reporting is not a condition of their permitting. James Cook University researchers have recommended expanding the current minke whale sightings reporting network to include all tour operators, not just those permitted for in-water encounters to better assess this issue8.

- Compliance with minimum distance regulations can be difficult, due to the whales’ apparent inquisitiveness5. Whales were shown to surface within 60m of a vessel more often than would be expected by chance and to cluster specifically around swimmers5. Individual whales tended to approach swimmers more closely over time within a single encounter and across subsequent encounters within a season6. This behaviour has the potential to place both humans and whales at risk – particularly if ‘swimmer experienced’ whales become more bold and curious over time.

- Recent studies have begun to shed light on the migratory patterns of dwarf minke whales, which are now known to migrate southward along the Australian continental shelf to the Southern Ocean after they leave the safety of Great Barrier Reef waters. Understanding the threats they may be exposed to whilst outside of the GBR is important to understanding how potential pressures from tourism may interact with threats they encounter during other parts of their life cycle to impact their overall well-being8.

For more information about swimming with minke whales in the Great Barrier Reef please consult: