Mexico: Laguna San Ignacio, Baja California Sur Alternative livelihoods and increased income for fishing communities

History and context

The landscape of Mexico’s Baja California Peninsula is arid and not naturally fertile. Traditionally, the region was sparsely populated by a few cattle ranchers and farmers, many of whom used artificial irrigation systems to eke out a living. However, the waters surrounding the peninsula, including a number of pristine lagoons, were teaming with life, offering sustenance and income to a number of small coastal fishing communities, including those near the Ojo de Liebre and San Ignacio lagoons. Blessed with rocky reefs, abundant fish and other marine life, these lagoons also serve as the wintering grounds for gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus), that feed in more northern waters of the Arctic and Pacific Oceans during summer months. Between December and March each year, whales gather in these lagoons to mate, give birth, and nurse their young. Numbers of whales have been steadily increasing since the ban on commercial whaling, returning to their estimated pre-hunting numbers in recent years1,2. This increase, coupled with the whales’ apparent comfort around vessels, has allowed these lagoons to become the focus of some of the earliest commercial whale watching tours, as well as dedicated whale research from the 1970s onward3,4.

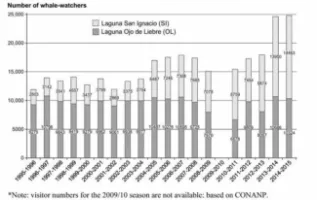

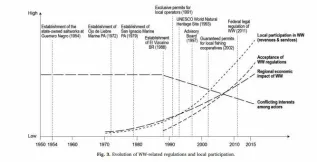

Whale watching activities in the region were initially driven by American tourists hosted by American tour operators who ran long-range live-aboard charter tours from California. Gradually, from the 1980s onward, local fishing communities began to establish their own whale watching companies and land-based camps5. In 1988, the El Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve (EVBR) was established. With a landmass of over 143,600 square km, it is the largest wildlife refuge in all of Latin America. Its surrounding waters encompass both the Ojo de Liebre and San Ignacio lagoons, which were evolving as two centres of whale watching activities. Throughout the 1990s the whale watching industry, run grew to accommodate thousands of visitors annually from all over the world3,4,6.

Table 1: Number of whale watchers in Laguna San Ignacio and Laguna Ojo de Liebre

|

|

2009-2010 |

2015-2016 |

2016-2017 |

2017-2018 |

2018-2019 |

|

L. San Ignacio |

6,683 |

7,093 |

6,598 |

7,366 |

12,558 |

|

L. Ojo de Liebre |

7,728 |

11,822 |

13,863 |

11,767 |

10,426 |

Source: EVBR, (note there is no available data for the 2014-2015 season)

In 2006 roughly 85% of all registered whale watching tourists in Mexico participated in tours in the Baja Peninsula, most of them in San Ignacio Lagoon3. A 2006 survey of tourists visiting the Vizcaino Biosphere reserve, found that 52% of all visitors considered whale watching as their primary or sole motivation for visiting the region6, while an additional 47% of interviewed tourists viewed whale watching as an attractive additional activity in the region. The majority of tourists were American, with just under a third coming from within Mexico and a smaller percentage from other (predominantly European) countries 6. This same study estimated that independent whale watching tours generated just under 3 million USD per year through direct and indirect expenditure in San Ignacio and the neighbouring town of Guerrero Negro (indirect including monies spent in local restaurants, accommodation and services in the community)5,6. Other studies generated higher estimates of up to 4.2 million USD per year in as early as 20027. This amount is likely to have increased significantly with increased numbers of tourists recorded from the 2013/14 season onward

Ensuring benefits for the local community as well as wildlife

Through the 1980s and early 1990s it was estimated that only 1.2% of total expenditures by whale watchers on package tours at San Ignacio Lagoon remained in the local community 6,8. Whale watching tours were predominantly run by American tour operators who travelled to the area in their own vessels and had little interaction with local communities. Furthermore, there was a concern that the large live-aboard vessels and close approaches being made by these vessels could be causing disturbance to the whales, particularly the mother-calf pairs that were resting and nursing in the lagoons 9.

From 1991 onward, new laws were put in place requiring foreign tour operators to use local whale watching tour guides to offer trips for their guests. Guiding tours from their own boats (locally known as pangas) offered fishermen an alternative source of income during the whale migration season when the use of fishing nets or traps that could pose an entanglement risk to whales was banned4,6. One study demonstrated that the income lost from a ban on rock lobster fishing during the whale migration in the Ojo de Liebre lagoon was 400,000 USD per year, but income from whale watching created 600,000 USD of income6. Another 2007 study of the economic impacts of whale watching found that the income from whale watching activities in the EVBR more than compensated the losses to fishing communities from the seasonal fishing bans5.

As of 2019, San Ignacio Lagoon, which encompasses 175 km2, hosted six local tour operators who made use of 26 licensed pangas. At any given time, a maximum of 16 pangas can operate, either individually or in collaboration with a maximum of two larger vessels that have to remain at anchor, rather than approaching the whales. Local tour operators participate in the Laguna Baja Asociación Rural de Interés Colectivo (ARIC).

The shift toward the use of local operators, who are supported by local restaurants, hotels and camps, has allowed the whale watching industry to become a significant source of income and employment for the local community, roughly doubling the number of whale watching associated jobs (for both men and women) between 1994 and 200210. A study conducted in 2007 estimated that roughly 18,000 whale-watchers generated a direct income of $0.7 million and generated 334 seasonal and 180 year-round jobs5 .

Lessons learned and recommendations for the future

- The success of whale watching in San Ignacio Lagoon and the wider EVBR is due mainly to the involvement of a range of stakeholders in its ongoing management and development. Researchers work hand in hand with local communities to monitor the population and understand its trends and conservation status2, as well as the potential impact of whale watching and underwater noise on the whales11,12. Tour operators are involved in designing regulations, and are represented in local conservation management bodies, ensuring that income and benefits from tourism activities are fed into the local community5, and this model is proving to help mitigate potential conflict and ensure transparency and consensus5.

- Clear, legally enforceable guidelines were established early in the industry’s development, using approach guidelines, standards for licensing of operators, and caps on the number of permitted operators and vessels allowed to operate in the region. Enforcement of these measures was facilitated by the designation of a protected area, with clear boundaries, within which surveillance and enforcement activities could take place5.

- Whale watching operators’ sense of involvement in management measures appears to contribute to a high level of compliance with whale watching guidelines13, presumably minimizing potential negative impacts on the whales.

- The strength of these collaborations has allowed stakeholders involved in conservation and the whale watching industry to collaborate to protect the breeding lagoons from other forms of development. This was the case in the late 1990s when plans were announced to expand a salt mining facility to include an additional 300 square kilometres of the San Ignacio Lagoon. NGOs and community members mounted a high profile campaign, including the involvement of celebrities who participated in whale watching tours to successfully lobby against this development.

Recommendations

- A recent survey of whale watching tourists in the San Ignacio and Ojo Liebre lagoons found a high level of satisfaction, with 100% of respondents rating their encounters as good, enriching, or marvelous, etc.14. However, in the same survey, local inhabitants rated some of the public services in the region as poor, with a lower percentage of direct employment opportunities in whale watching than desired, particularly for women14. The income from whale watching should contribute to improvement of public services for the locals, and ideally, as one of the main economic generators for the region, whale watching should create even more direct employment opportunities for locals.

- As tourism numbers increase and the conservation challenges become more complex, it will be important to ensure that community stakeholders have the skills and support that they need to effectively engage in ongoing monitoring and management of the industry. Leadership and management skills are required at all levels and from all stakeholders ranging from local and regional government agencies, to community leaders and representatives15.

- Likewise, vigilance will be required to ensure that the management measures and guidelines that are in place are adequate to protect the whales and their habitats from potentially negative impacts or additional threats in the face of climate change and pressures that they face outside of their protected breeding grounds. Mass mortality events of gray whales 16,17 in the past 20 years, as well as mortality from fisheries entanglement in other parts of their range18, as well as the relatively recent discovery that the San Ignacio Lagoon hosts individuals from the endangered western gray whale population that feeds off the Sakhalin Islands in Russia19 may require extra vigilance and care on the population’s breeding grounds. Scientific studies should continue to monitor the potential impact of whale watching, to ensure that stress from persistent vessel interactions or masking of communication from underwater noise associated with whale watching do not compromise the whales’ welfare in the long run.

For more information about whale watching in San Ignacio see:

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/photography/proof/2017/08/gray-whales-baja-mexico/