Dominican Republic: Samaná Bay The strengths and challenges of co-management of whale watching

History and context

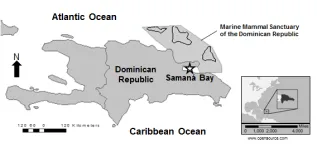

The Dominican Republic (DR), which occupies half of the island of Hispaniola, has the largest whale-watching industry in the Caribbean1,2. Whale watching in the DR was first established in 1985 from the town of Santa Barbara de Samaná (from here on referred to as Samaná). At this time, an expatriate tour operator, began to take mostly foreign tourists out to see the humpback whales that visit Samaná bay between January and March each year to mate, give birth, and nurse their young. Many more tour operators followed, and in a short time Samaná became the a whale-watching hub, both for day tours in Samaná bay, and as a harbor visited by some of the longer live-aboard tours that take visitors out to the offshore marine mammal sanctuaries of Silver Banks (established in 1986) and Navidad Banks (established in 1996). These two sanctuaries, along with the nearshore area of Samaná cover a total area of 25,000 square km and are jointly referred to as the Marine Mammal Sanctuary of the Dominican Republic (MMSDR).

As of 2008, there were 33 whale-watching companies and 46 permitted vessels1 registered in Samaná, a town of approximately 100,000 permanent inhabitants. By 2012, over 40,000 people engaged in whale watching in the marine mammal sanctuary during the humpback whale breeding season3 with over 90% of all whale-watchers in Samaná being international tourists1.

Live aboard tours to Silver and Navidad Banks, over 100km offshore, are expensive and as of 2008 attracted only an estimated 500 tourists per year1. Tours in Samaná Bay, however, are more accessible, and can fall into one of three categories:

- Tours on small wooden or fiberglass vessels with outboard engines called yolas. At a maximum length of 9 metres, and maximum capacity for 10 passengers, these trips are informal, with no fixed departure times, and no formal guides or interpreters3.

- Marine tours that involve short interactions with whales, and then continue to take tourists to the local resort island of Cayo Levantado for lunch, shopping and beach time. These tours are offered on lanchas (9 -11 m) or barcos (>11m). These operators tend to be licensed, and are often engaged through tour companies or cruise ships as part of pre-packaged tours.

- A dedicated whale watching tour with trained naturalists on board, a strong educational element and interpretation during whale encounters. Currently only one company in Samaná offers this type of tour.

Since 2009 cruise ships have been coming to Samaná as part of wider Caribbean tours. Each ship brings hundreds of tourists, many of whom wish to engage in pre-arranged package tours that include a 2-3 hour boat excursion. This recent development has had an impact on the dynamics of whale watching tours that are offered3.

Regulations and management measures

In its first few years whale watch tourism in the Dominican Republic was not regulated. In 1992 two non-profit organizations were concerned that boat behaviour was causing disturbance to the whales, and they cooperated to draft voluntary whale watching guidelines. Although these were adopted by the boat owners’ association in 1994, compliance was low. As such, the Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Tourism, the whale-watching boat owners association (ASDUBAHISA), the Dominican Navy, and El Centro para la Conservación y Ecodesarrollo de la Bahía de Samaná y su Entorno (CEBSE), a local marine conservation non-profit all came together to form a co-management system for whale watching in Samaná Bay. This system included measures for permitting operators, monitoring boat behavior, surveillance, enforcement and self-sustaining finance for administration and personnel costs1.

The regulations established in 1998 have been revised on a few occasions; the most recent revision was on May 2018. They now entail the following key measures:

- No more than three boats may watch a whale group at a time;

- Boats waiting must maintain a distance of 250 meters from the whales;

- Vessels must maintain a minimum distance of 50m from adult whales and 80 m from a group with a calf;

- A vessel may spend a maximum of 30 minutes with one group of whales if other boats are waiting;

- Vessels may travel no faster than 9km/hr (5 knots) once in the sanctuary, or whenever a whale is observed outside the sanctuary;

- Vessels must depart the Sanctuary by 16:00 each day;

- Swimming with whales is prohibited in Samaná Bay;

- All passengers on boats less than 10 m length must wear life jackets all times;

- A maximum of 43 permits for WW are awarded in Samaná;

- All boats engaging in whale watching must pass inspection by Navy officers and Ministry of Environment experts (e.g. hull integrity, VHF radio and other safety measures on board).

In 2018, there were 56 boats with permits in Samaná Bay. Some of them have “regular” permits that allow them to whale watch continuously, while some have “rotative” permits which are shared by various boats and allow them to whale watch only one day at a time each. As a result of issuance of authorizations, the maximum number of 43 botes/lanchas for WW operating in Bahia de Samana is maintained.

Once permitted, a vessel is issued a flag that allows it to be identified as an officially recognized whale watching boat. Permit fees are used to help fund the administration and running of the co-management system, which requires monitoring and surveillance. Monitoring is conducted by government appointed inspectors/observers who accompany tours on licensed vessels and are mandated to report any infractions to the Navy. A Ministry of Environment/Sanctuary Administration vessel also patrols the whale watching area, and this vessel as well as the Navy has the right to issue sanctions as follows:

- Tourists without life jackets, no VHF radio, approaching whales too closely: 3 days enforced in port

- Violations of waiting turns to approach whales, or whale watching without a permit: 5 days in port

- 3 of one of the above sanctions within one season: Permit rescinded for the rest of the season

- Aggression towards an observer or enforcement personnel or collision with whale due to reckless boat handling: permanent cancellation of permit.

Less formal monitoring of whale watching is conducted by the non-profit organization - CEBSE who facilitate the placement of (usually student) volunteers onboard whale watching vessels collect basic data such as whale sighting locations, and duration of encounters. These volunteers also take pictures of flukes (tails) and dorsal fins for the identification of humpback whales. This data is entered into a photo-identification database that is maintained CEBSE.

Lessons learned

The management of whale watching in Samaná Bay offers an example of a co-management framework that in many respects includes all the elements that should lead to success.

Strengths

- The system was developed by local stakeholders who recognized a need to better regulate activities to protect the whales. As such, there is a sense of local ownership for the system;

- The co-management system involves a wide range of stake holders, including government bodies, enforcement agencies, boat owners, tourism development agencies, and local NGO’s. In this sense, a broad range of interests and perspectives should be represented in discussions and decision-making;

- The permitting fees generate revenue for the administration and implementation of the co-management system – allowing it to theoretically be self-sustaining;

- The regulations are clearly defined, as are sanctions for infractions. A monitoring and surveillance system is in place, as are mechanisms for issuing sanctions when infractions incur.

Many whale watching locations around the globe struggle to put such clear mechanisms in place, and these can serve as a model to other areas interested in establishing a co-management system. However, as with most systems, implementation in the field is not always as clear-cut as the design appears to be on paper. The system recognizes a number of challenges, from which others can learn:

Challenges

- Not all stakeholders feel that their concerns and interests are equally represented. Some (local/indigenous) smaller boat owners feel that it is difficult to have their voices heard when larger boat owners and tour operators have more frequent contact with government agencies and/or the tourism booking agencies that arrange package tours for foreign tourists. Ideally, the system could adapt to make sure that smaller businesses/boat owners can profit from the industry and feel well represented3;

- The increasing number of cruise ships since 2009 has led to further perceived favouring of the larger tour companies with larger vessels who offer general sight-seeing boat trips in Samaná Bay. These are pre-contracted by the cruise ship companies, and participating tourists are usually under strict time pressure to return to the ship and/or enjoy some time on land before returning to the ship. As a consequence, the boat captains feel pressure to find the whales and get their guests as close to them as possible as quickly as possible. This is leading to more infractions of approach guidelines, and a greater sense of frustration from other operators who either feel excluded from the cruise ship business or wish to see greater respect for approach guidelines3.

- Only some of the 43 licensed whale watching operators regularly include a strong educational element in their tours. The education of participants is widely recognised as one of the potential conservation benefits of whale watching 2,4-8, and it has also been recognized as something that tourists value in a whale-watching tour9-11. A recent study found that over 80% of interviewed tourists in Samaná Bay ranked the importance of public education on whale conservation as high or very high12. The study strongly recommends that practices in Samana be adapted to ensure that very whale watching boat has an interpreter/guide present who can present basic information about whale behaviour, ecology and conservation need12.

For more information about management of whale watching in the Dominican Republic please consult: